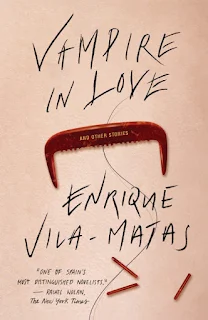

The first collection of Vila-Matas' short stories in English translation is named after the fifteenth story in the table of contents, but might better have been named after the seventh, Death by Saudade because it compresses Vila-Matas' work into a black hole. Just as Harvill Secker’s abbreviation of Montano’s Malady, his second novel in English, excludes any mention of illness, the choice of this title disguises the nature of his fiction with a predictable play on genre.

This is entirely understandable, as publishers must assume potential consumers read for what is misnamed 'entertainment' rather than to assuage saudade, a Portuguese term with no equivalent in English but defined by Wikipedia as "a profound melancholic longing for an absent something or someone that one loves". Indeed, to misquote Kafka, we might wonder how can one take delight in stories unless one flees to them for refuge. There's the extra worry for the publisher in that potential readers are notoriously resistant to short stories, as they minimise the pleasures of following a character as they traverse deep time. To mitigate this, short stories are narrated more often than not in the first person, with Vampire in Love no exception.

Death by Saudade in particular is narrated by the owner of a dry-cleaning shop telling of his childhood fascination with the plenitude that lay beyond home and school, inspired by a friend's stories of his seafaring grandfather. Watching the activity on a busy street replaced reading great novels, he says. He becomes intrigued by a female vagrant who approaches women and appears to whisper something in their ear. To hear it himself he dresses up in his mother's clothes but, rather than hear any exciting secret, he is seized by her "wild, magnetic, mirror-like eyes" and feels a gust of wind on his face:

You might think all this means Vila-Matas' fiction is negative, not life affirming, depressing even; everything 'entertainment' seeks to repress. This is because Vila-Matas is attuned to the enigma of fiction, of this strange need to read and write – projected here into travel and painting. His fiction shadows its logic. Why, after all, has the dry cleaner spoken at all? And why are we listening in this way? The issue of the story before us is neither whether the narrator is convincing, reliable or anything else, nor whether the form of his narration is traditional, experimental, modernist or postmodernist, but the paradox of saudade: a word whose meaning requires translation even in its language of origin, a condition that is magnetic and mirror-like, pinning the sufferer to mortality and reflecting their denial, and yet that which gives life purpose and meaning, which returns us to the child wanting to discover what is beyond and so to fictionalise himself as a woman to do so, then to duplicate the breeze in paint, and so to accommodate it, to make life and death indistinguishable. Life by saudade.

His friend finally reveals that his seafaring grandfather had in fact killed himself, and later the narrator discovers that numerous other members of the same family had also killed themselves. They had succumbed to saudade and "experienced the only possible plenitude, the plenitude of suicide". Vila-Matas' comedy is never far away.

The paradox of saudade is then the paradox of reading and writing. At the end, the narrator says he will not leap into the void, while the story demonstrates otherwise.

This is entirely understandable, as publishers must assume potential consumers read for what is misnamed 'entertainment' rather than to assuage saudade, a Portuguese term with no equivalent in English but defined by Wikipedia as "a profound melancholic longing for an absent something or someone that one loves". Indeed, to misquote Kafka, we might wonder how can one take delight in stories unless one flees to them for refuge. There's the extra worry for the publisher in that potential readers are notoriously resistant to short stories, as they minimise the pleasures of following a character as they traverse deep time. To mitigate this, short stories are narrated more often than not in the first person, with Vampire in Love no exception.

Death by Saudade in particular is narrated by the owner of a dry-cleaning shop telling of his childhood fascination with the plenitude that lay beyond home and school, inspired by a friend's stories of his seafaring grandfather. Watching the activity on a busy street replaced reading great novels, he says. He becomes intrigued by a female vagrant who approaches women and appears to whisper something in their ear. To hear it himself he dresses up in his mother's clothes but, rather than hear any exciting secret, he is seized by her "wild, magnetic, mirror-like eyes" and feels a gust of wind on his face:

"I fled in terror because I had suddenly understood that what I had just seen, with utter clarity, was the face of the evil ravaging the streets of the city and which my parents, in low, cautious voices, called the wind from the bay, the wind that drove so many mad." [Translated by Margaret Jull Costa]From then on and into adulthood he feels like a vagrant himself, travelling to evade anxiety and melancholy all the while "filled with the temptation to leap into the void". He walks through the city of Bernardo Soares full of beautiful places to make the leap. Back home he tries to paint what he saw on the street but never finishes anything. The plenitude that promised so much in childhood is revealed as something else: "I say to myself that life is not achievable while one is alive".

|

| Saudade (1899) by Almeida Júnior (note that she is reading) |

His friend finally reveals that his seafaring grandfather had in fact killed himself, and later the narrator discovers that numerous other members of the same family had also killed themselves. They had succumbed to saudade and "experienced the only possible plenitude, the plenitude of suicide". Vila-Matas' comedy is never far away.

The paradox of saudade is then the paradox of reading and writing. At the end, the narrator says he will not leap into the void, while the story demonstrates otherwise.